How to help teenagers talk to, and about, AI

Lessons from six days of AI literacy with Gen Z and Gen Alpha in NYC, Portugal, and England

In the last 10 days I co-designed and led 26 hours of AI literacy for teenagers in 3 countries. Here’s what we did and what I learned.

First, some quick context: The first 20 hours took place in person over four days in New York City, in collaboration with Matthew Baldwin Associates. The final 6 hours took place online over two days with students in Portugal and England, in collaboration with The Teenhood, alongside AI and child rights expert Louise Hooper. I’m grateful to have had the chance to work with two great organizations and teams!

Here are three activities that resonated for students, and why I think they did.

A Brief History of AI: WWII to 2022

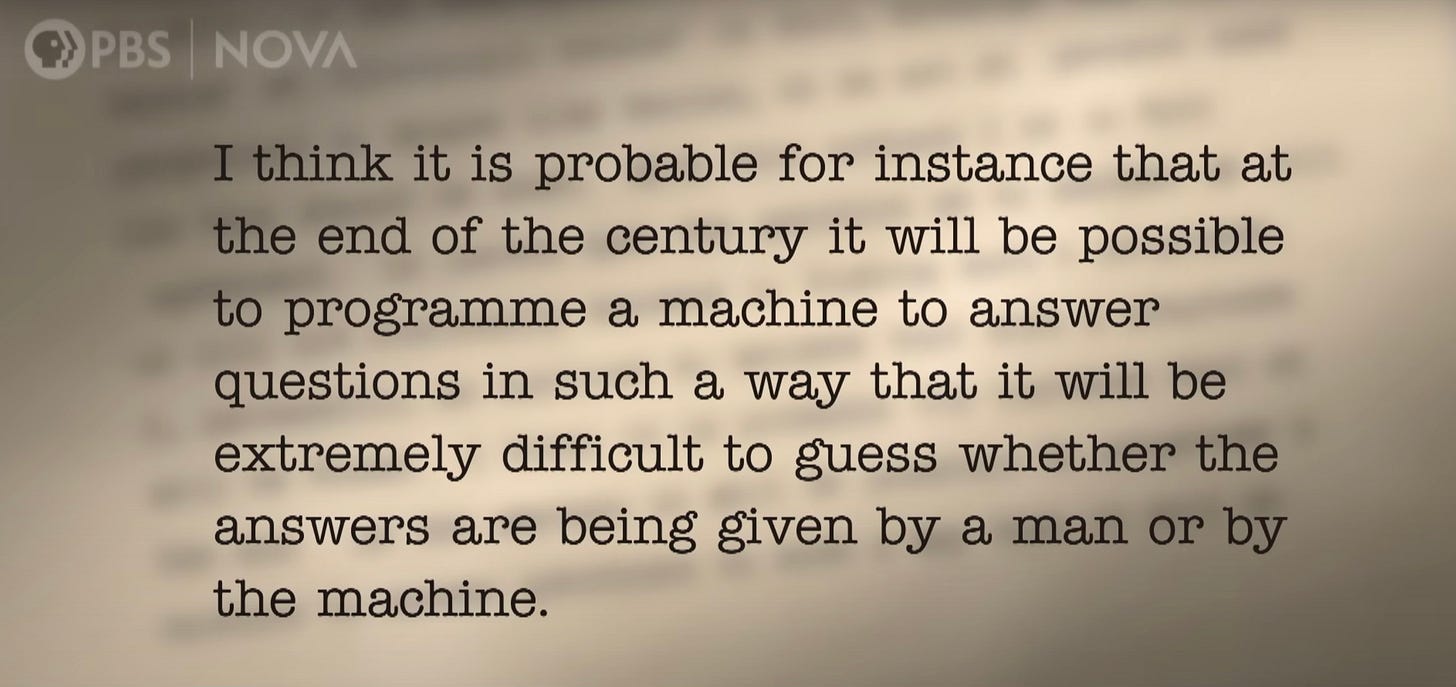

We watched 11 minutes from a 2024 PBS documentary on AI (5:40-16:20 to be precise). This clip starts with WWII codebreaking machines and Turing’s 1951 prediction:

It then moves through Deep Blue beating Kasparov at chess in 1997 and AlphaGo beating Sedol at Go in 2016. It concludes with the launch of ChatGPT in 2022.

Both times I showed the clip, I was again struck by how AI seems like a sudden, recent phenomenon to many young people. It often appears to them as a sort of deus ex machina that has descended onto the world stage since the end of the pandemic.

When they see and discuss the history behind today’s AI tools, they gain several valuable insights in less than half an hour:

Gen AI models and tools are part of a long progression of technological development that has taken many generations to accomplish. It was striking to students to see a black and white photo of Turing, for them a man from a totally different epoch, and then hear him basically predict the LLMs they see today.

From the start, modern AI and its predecessor systems were predicated on the simplification and quantification of our world. For example, students were interested (and often delighted) to learn how big a role video games and board games played in the development of AI. In a sense, AI reduces reality to rules.

The major AI labs, and our modern AI industry as a whole, seem to prefer maintaining the impression both that AI is their recent creation and that LLMs are increasingly lifelike. In other words, the zeitgeist surrounding students is at odds with the reality of this technology and its history.

When students put that all together during our discussions following the clip, you could almost hear new ideas clicking into place, giving them a clearer perspective on our AI moment. In a sense, it was only when they grasped the broader scope of AI that they started to feel they could actually get a handle on it.

In other words, when young people demythologize AI tools and AI companies, they realize this is just another human story and therefore one in which they have a part to play. One of the largest parts, in fact, since they’re the ones who will live through this the longest and have the most decisions to make.

I use the word “demythologize” intentionally here. AI as a concept and a technology has achieved somewhat mythic status in some conversations, including ones young people are hearing. And there’s also at times a tendency to mythologize the companies and people creating our AI tools.

All the more reason to remind students that, though the impact of AI may well be titanic, its creators are not titans. They are fellow humans, and therefore young people have the right (and perhaps duty) to evaluate and question their decisions.

LLMs 101: Models Within Models

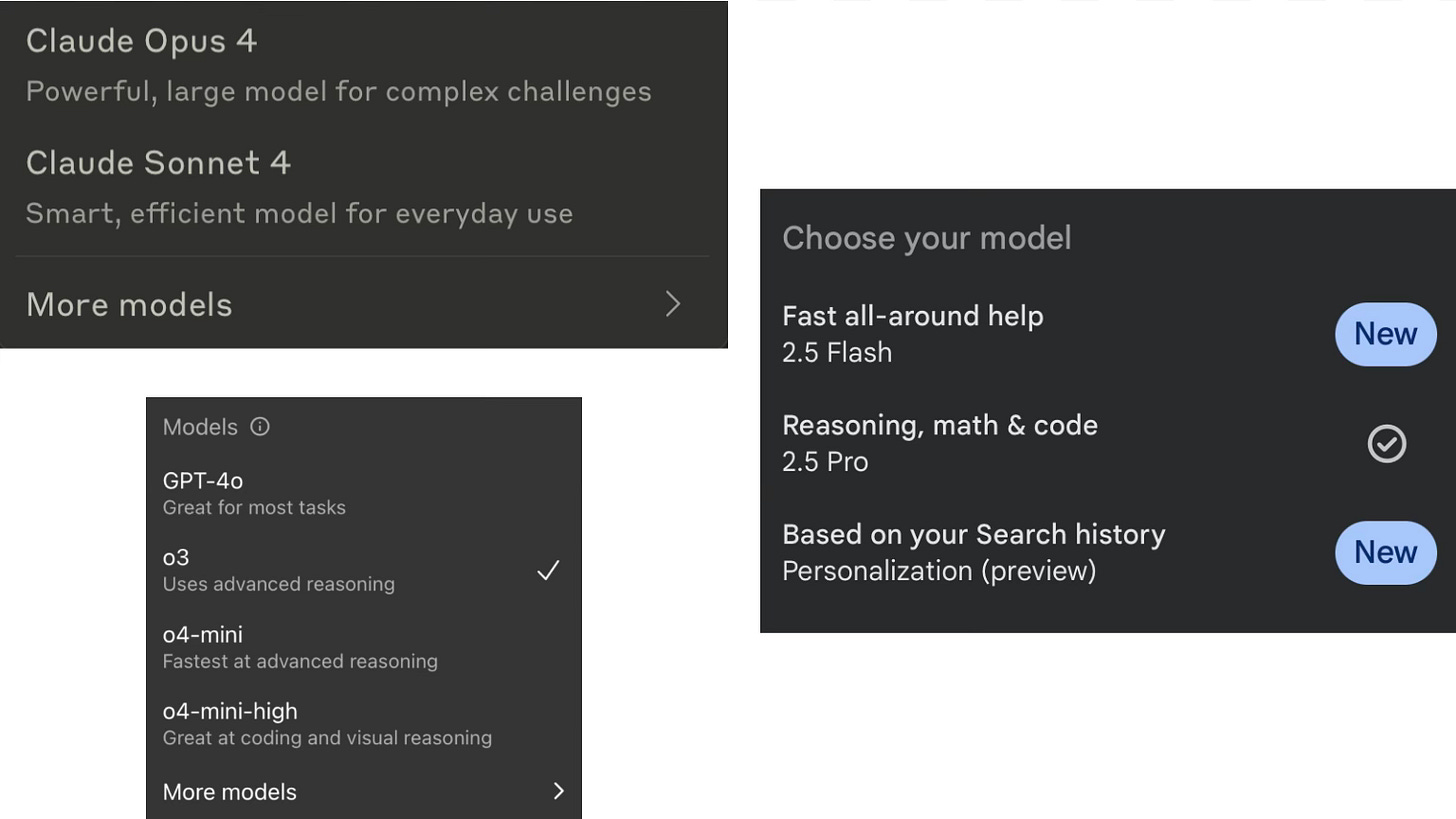

We reviewed the difference between the three frontier models (GPT, Claude, and Gemini) and the emerging best use cases for each. We then looked at the specific models within each, and how to choose the best one for various tasks. (We also explored the deep research, speech, and projects functions.)

Watching students discover those technical details reminded me of watching students learn to Google effectively. In both cases, it can be surprising to see students who fly around their phones at light speed can get tripped up by basic structural considerations like how to formulate a Google search or how to strategically leverage the capacities of frontier LLMs.

But then I remembered my first early teaching job, training as an English language instructor in Rome one summer in college. As I worked with Italians struggling to speak English during the day and then struggled myself to speak Italian at night, it became clear that understanding grammar and being fluent are not the same thing.

The rising generation of digital native speakers benefits from learning digital grammar. Among other things, that gives them a simple but important form of AI agency — the ability to choose the tool to match the task.

The Power of Parable

We watched clips from the prescient 2013 film Her, starring Joaquin Phoenix and Scarlett Johansson. In the film, the protagonist slowly falls in love with a lifelike AI system named Samantha that he mostly communicates with via an earbud. As we watched, we considered questions like:

Is this a healthy relationship?

What’s the difference between these conversations and a series of phone calls with a partner living overseas?

Does the movie end happily? For whom?

Like all great art, Her helps students feel (not just conceptualize) what talking to AI tools might be like in the near future. The complexities coming soon on this front are exactly the kind of knot the humanities can help young people start to untangle.

In between watching sections of the movie, I spoke live with GPT’s “Sol” voice, which has a more than passing resemblance to Samantha’s voice in the movie. At one point, I demonstrated the voice-plus-camera feature to play “I Spy” with nearby objects. We also watched a recent CBS Mornings report about real people falling in love with AI and read parts of a recent NYT article about chatbot therapy. Afterwards, we discussed:

How close is this technology to what the movie is showing?

Will we see more people falling in love with AI voices?

Is there any benefit to AI companionship or therapy?

Students became aware of broader, long-term implications of AI and simultaneously also aware that those implications aren’t inevitable. They have a say about what happens regarding, for example, the verisimilitude of AI voices or the question of AI product liability.

Final Reflections

In all of those moments, and in many others that made up both AI literacy programs, we came back to reflection. We’d often do hand-written reflections on paper and then share and discuss after. In this AI moment, there’s something even more powerful than usual about writing by hand and taking time to think.

In that spirit, some final reflections:

AI literacy needs to be multidimensional.

We’ll need the humanities as much as the sciences and social sciences to help make sense of all this. We’re in an all-hands-on-deck moment and need to assemble all our modes of thought, partly because every student will find a different angle on AI that works better for them.

Conversation is crucial.

Some moments in AI literacy work need to be teacher-led, guided-practice style experiences. Other moments should be hands-on, even if it’s the teacher using AI as the students guide them. But those two kinds of moments should be less than 70% of any AI literacy scope and sequence. In my experience, at least a third of the time students spend learning about AI should be spent talking about it, in relation to themselves and their futures.

Young people aren’t sure yet what to make of AI.

They’ve been as disoriented as the rest of us by the speed of the tech’s improvement and the dizzying array of opinions surrounding it. We need to help them find their footing, by giving them more context and also helping them develop their own opinions about all this.

But they’re eager to talk about it.

As always, young people love debating complicated topics that have personal implications. And since this topic feels simultaneously omnipresent and distant, they were even more eager than usual to dive into our conversations. Having led a lot of classroom conversations over the past 20 years, I was struck by how this one needs very little encouragement to get rolling, and soon takes on a momentum of its own. Gen Z and Gen Alpha are ready to weigh in.

If our AI in education efforts so far have sometimes felt like the blind leading the blind, let’s give our students some light to see by — and then see where they lead us.

Mike - the PBS doc is a great resource. Thx. Your work overlaps a lot with what I've been doing (or trying to do) at my school in Westchester. Mike Whitaker pointed me to your Substack - would love to set up a visit to see how your approaching and discussing AI at Uncommon Schools in Brooklyn. Great work.

https://fitzyhistory.substack.com/